Julia Garrison

Gianna Hayes

News Editors

Zach Perrier

Viewpoints Editor

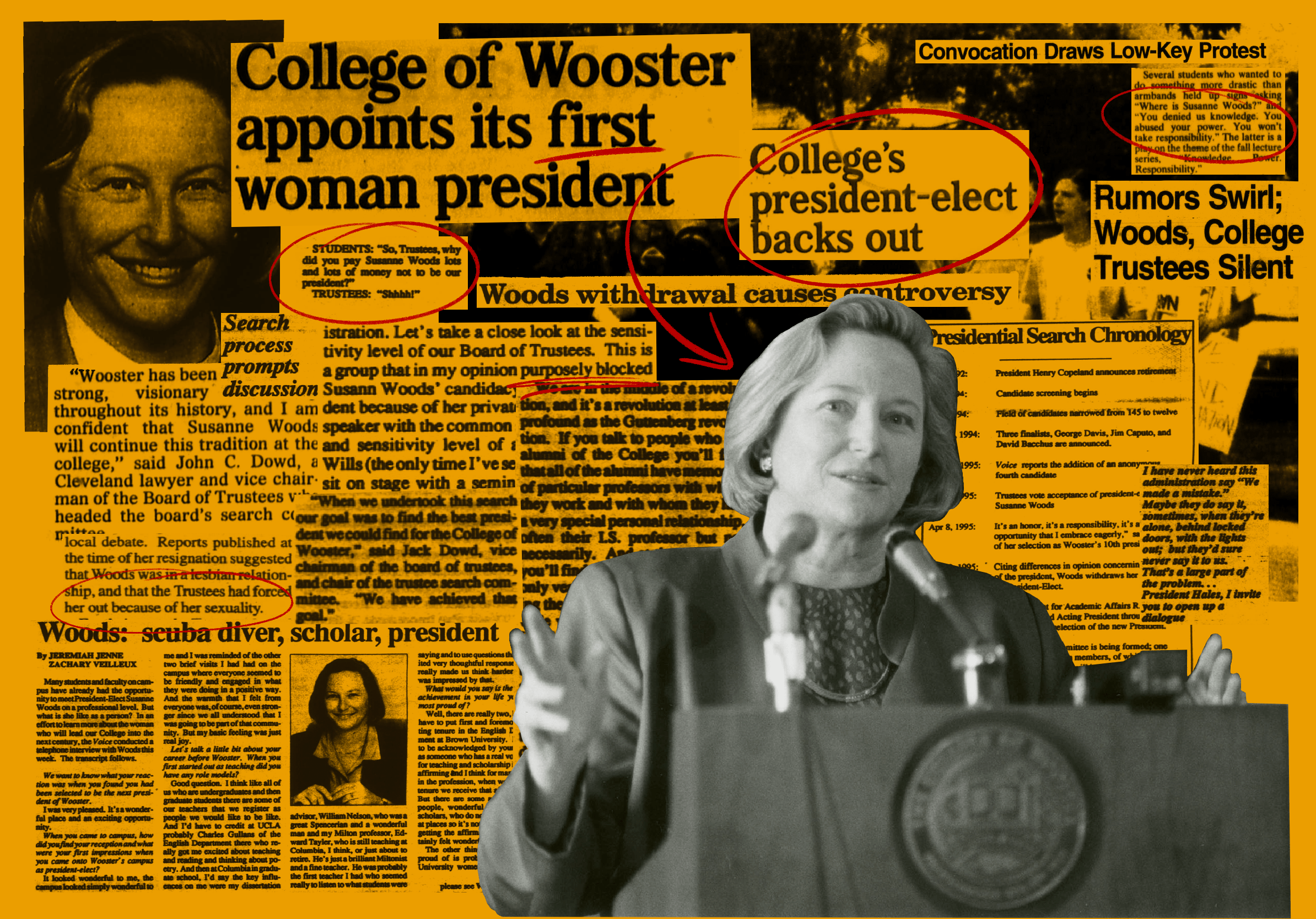

“WHY ARE STUDENTS WEARING PURPLE?” read a small slip of paper that senior Robyn Perrin ’96, wearing a purple armband, passed out to attendees of Wooster’s 1995 Convocation. Over 100 other members of the community wore the same adornment, holding signs asking: “What happened to Woods?”

The end of an era

Henry Copeland was set to retire. Copeland had given 32 years of his life to the College as a professor, administrator and president. Shortly after the 1992 announcement of his retirement, the hunt for Wooster’s 10th president began.

The presidency had been localized for years before Copeland’s retirement, as faculty, alumni and trustees often took the role. The College and the trustees were ready for a new face to serve the community.

In 1994, the presidential search committee was formed, which included eight trustees and eight faculty members — no students or staff — and was led by Jack Dowd, the vice chairman of the board of trustees. Among these faculty members were Madonna Hettinger, Mark Wilson and Ron Hustwit.

“These were the worst days of my life,” Wilson said in an interview with Jerrold Footlick ’56 for his compiled history of Wooster, “An Adventure in Education.” Wilson expressed disdain for his time in the search committee because of its eventual disintegration and a negative faculty response, which was spurred on by the selection of younger faculty members to the committee over older, tenured professors. The faculty as a collective voted for their representatives to the committee and chose Wilson to serve as their chairman and liaison.

Hettinger described the search process as one of the best experiences “working in a group that had different perspectives but the same interest in the mission of the College.” Hettinger was new to Wooster and notably had not received tenure until halfway through the search process.

The committee also gained the help of John Phillips — a former chief of the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities — as a consultant who was well-regarded in the world of higher education. With the help of Phillips, the committee narrowed the search from 150 candidates to three.

The candidates included an alumnus of the College, a congressman and a professional in academia. Yet the search committee could not agree on any of these candidates and was left still searching for Wooster’s next president.

Hustwit resigned from the search committee out of frustration, urging the committee to “either back out of the mess by appointing [the alumnus] or restart the search.” Amidst the confusion of the deadlock, and the removal of all prior candidates from the search, Phillips introduced a new candidate to the committee: Susanne Woods.

A new candidate emerges

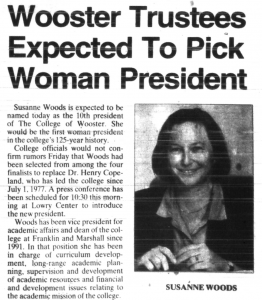

Woods hailed from Hawaii with degrees in political science and English from the University of California, Los Angeles and a doctorate in English and comparative literature from Columbia University. She had worked at Brown University for 19 years as an English professor, and more recently had become provost at Franklin & Marshall College.

Woods initially declined the nomination for the presidency due to obligations in curriculum changes at Franklin & Marshall, but by March 1995 had shown renewed interest in the position and quickly became the committee’s top choice, emerging as a finalist in late March.

“She pushed all the right faculty buttons,” explained Wilson. “I was [just] so relieved that a good person had appeared — after what seemed to be a failed search.”

“She walked in and you could see it in the room, everyone was sitting up straight, and everybody was ready to lean in,” Hettinger said, recounting Woods’ refreshing interview after a long and frustrating search process. “She ‘got us.’”

On April 6, 1995, only a month after her emergence as a finalist, Woods was nominated for the presidency by the board of trustees in a special session in the afternoon. She would be Wooster’s 10th — and first female — president.

In an unpublished interview with Woods for Wooster Magazine, she explained the importance of introducing a female president to a campus like Wooster. “We do bring a somewhat different experience to whatever job we undertake than do men,” she explained. “I want to be a spokesperson for liberal arts in an absolutely crucial time in our history, and I am just thrilled to have the opportunity to do this with The College of Wooster.”

Shortly after becoming president-elect, Woods met with selected student leaders on campus. “I thought she was fantastic. She was very humorous and witty but also very intellectual. She listened intently to what everyone said,” Betsy Beyer ’97 told the Voice at the time. In a telephone interview with the Voice later that month, Woods reflected on her visits by saying “the warmth I felt from everyone was … even stronger since we all understood that I was going to be part of that community.”

Set to take office on July 1, 1995, Woods would be joining the historic ranks of seven other female presidents in northeast Ohio, a marker in Wooster’s history that drew attention to the College. The community reception of Woods’ presidency was overwhelmingly positive, with glowing reviews from faculty, administrators, students and members of the search committee. However, Woods never took office.

Search committee questions left unanswered

On April 21, 1995, the Voice reported on a meeting with faculty and hourly staff members to air grievances regarding the presidential search after its completion. The moderator of the meeting was James Perley, professor of biology and president of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) from 1994 to 1998.

Perley criticized the “way faculty were represented in the search,” and pushed efforts to create a local AAUP chapter at Wooster. Chair of the hourly staff committee, Diane Fossey, echoed these sentiments, concerned that no members of Wooster’s hourly staff or students were included in the decision-making process.

From the beginning of the search, a roundtable of faculty conferred at Lowry Center to voice their concerns with the search committee. At one of these “anti-committee” meetings, Perley offered a telephone directory from Denison University to meeting attendees, where a professor of English named Anne Shaver listed Susanne Woods as her partner. “I had no problem, just curious,” Wilson recalled Perley saying.

During the search process, Woods stated that she was “single by choice.” In interviews with Footlick for his book, some professors, such as Jennifer Hayward, took Woods’ comments as an implication that she was gay. Susan Figge, one of the founders of the College’s women’s studies program, had also mentioned in passing during her interview with Footlick the circulation of an anonymous letter saying Woods was a lesbian. Wilson later offered that the faculty were aware of her speculated identity during the search process; however, the trustees were not.

The chairman of the board of trustees, Stan Gault, explained that he had never asked Woods about her relationship to Shaver as it seemed unprofessional. “[Woods] volunteered to me that what had been brought to our attention was incorrect,” explained Gault about the “information” that Woods was a lesbian. “In my mind, I doubt that.”

Some faculty who were not aware said that Woods had lied to them. “People like me opposed her not for her lifestyle but as [a] liar,” said professor of history emeritus John Gates. Special counsel to the College Lincoln Oviatt told Footlick, “[Gault] was lied to. And you don’t lie to Stan Gault.”

Administrators scramble to fill an empty seat

In late June, the trustees and Woods had decided that she would not become the next president of Wooster. On June 30, a day before she was to take office, Woods withdrew from the position. In an announcement by Gault, the reasons for this withdrawal were purportedly due to differences “that Dr. Woods and members of the Board could not resolve.”

Woods and members of the board of trustees signed confidentiality agreements stipulating that they could not give statements about the situation, and a severance package was also paid to Woods over a 24-month period. The severance package was entirely paid for by Gault and did not appear on the College’s official tax records.

In a private conversation, Gault informed then Vice President for Academic Affairs R. Stanton Hales in late June that Woods would not be the College’s president. Gault then asked Hales to be the acting president for the academic year. Hales remembered saying, “well, boy, this is a bit of a surprise.”

The search committee was asked to reassemble after the announcement of Woods’ withdrawal; however, many of the original faculty committee members declined. A new search committee was formed, this time with four faculty members, no faculty chair, eight members of the board of trustees, two students and a new presidential search advisor.

An August article published in The Chronicle of Higher Education sparked a national conversation about the disappearance of Woods from Wooster’s administration. The article included anonymous sources who speculated that Woods withdrew from the presidency because some of the trustees “balked after learning details about her long-term relationship with a woman.”

“Why are students wearing purple?”

The controversy from the summer months was revived in the fall as students arrived back to campus. Students received little to no explanation on Woods’ departure from the College, creating more questions than answers.

Dowd urged that there was “no prejudice” involved in the resignation and none of the rumors that he heard were correct, but this wasn’t enough for students, and their dissatisfaction led to protest. Students gathered in the Lowry Pit two nights before Convocation in August to discuss Woods’ withdrawal, and a protest was organized.

At Convocation, organizers passed out purple armbands to protestors in response to the College’s lack of transparency. Some protestors created signs with phrases such as, “WE DEMAND INFORMATION.”

Accompanying the protest were handouts that outlined grievances and confusion surrounding the silence from the College. The handout voiced concerns about Woods’ abrupt rescindment of the presidency.

– 1995 Convocation handouts“Amazingly, even though Wooster has proudly proclaimed that it is a stronghold of ‘politically correct’ viewpoints and a champion of minority rights, neither appear to apply to their hiring practices. This incident has damaged Wooster’s reputation greatly in a way that will be painfully difficult to repair. We mourn the lack of information that has surrounded this event and the rifts that it has caused throughout the College community.”

“At the time, as a student [I asked], ‘why are they giving these nondescript, blanketed answers?” Jessica Harbeson (then Nelson) ’97 recalled. “The administration was not telling us what was going on, and students were concerned about possible discrimination.” Harbeson was the president of the Gay Lesbian Bisexual Alliance (GLBA) at the time.

After urging protestors at Convocation to meet with him personally to address and understand their concerns, Hales met with Perrin and Harbeson for a private meeting. “[Hales] was in a tough position in trying to do his job … he was not able to put those concerns to rest. He was not able to say what students wanted him to say,” Harbeson added.

Perrin explained that concerned community members were still interested in protesting throughout the entirety of the academic year following the announcement. A portion of the graduating class of 1996 also wore purple ribbons on their gowns as a form of protest. Perrin was among these students.

“We thought [Woods] would be speaking [at graduation],” she added. Perrin also wrote an email to the College criticizing Georgia Nugent’s billing as Wooster’s first woman president when she became interim president in 2015. Perrin explained in the email: “as students, we did try to make our protests heard, to little effect.”

Alumni and faculty attest to the lingering memory of the incident. “I haven’t been as engaged, and every time [there are alumni gatherings], I do think about the Woods incident,” said Perrin.

Figge recounted the moment faculty became aware of Woods’ forced withdrawal, saying that she and Professor of English Deb Hilty “wept together” in her office.

A lingering presence on campus and beyond

In the years since Woods’ withdrawal, the story of what had happened has continued to resurface. Professor of English Nancy Grace recalled in 2012 that students still stumbled across the story and that candidates for presidential searches asked what had happened.

Interim Dean of Faculty Development and Department Chair of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Christa Craven explained that the history of Woods “was always kind of haunting me as I went through reviews, went up for tenure, went up for promotion, knowing that history was there and wondering whether I would be at any point let go … for similar reasons.”

Craven also mentioned a photograph archived in the women’s, gender and sexuality department digital history project that was anonymously given to her when she became dean. “The person who gave it to me — they had been told to destroy all of the photos and the negatives by an administrator at that time — but had kept this one, had put it in a briefcase and knew this was going to be important someday.” A copy of the photograph is also available in the College’s Special Collections. “There were many in the administration and the board of trustees at the time who really wanted to pretend that it never happened.”

Speaking with Footlick, Gault said “Oh, I really don’t think it did hurt the college because, fortunately because of the way it was handled, including in the communication and the financial aspect of it, it never became a major issue. In fact, you almost have to go back and say, ‘Did that happen? I don’t recall that.’”

The impact that Woods would have had as a woman president was sorely missed, especially by women faculty and students. “It would have meant a lot to that generation of students,” said Hettinger.

“It was … a lasting trauma for women … a signal that women’s leadership could be stigmatized at an institution of liberal learning that professed strong egalitarianism and strong beliefs and pursuit of women’s participation at every level of academia and society,” Hans Johnson ’92 explained.

Alumni ultimately feel that the College should be more candid about Woods’ sudden departure going forward. Perrin emphasized that “[it would be] helpful for the College to simply acknowledge what happened with the most transparency they are able to give.” Harbeson concurred, saying that, regardless of the situation, “the more you say, the less people are going to feel hurt and worried.”

To Johnson and other alumni, the loss of Woods felt like “a gut-punch, like a loss in the family — like a signal of unwelcome to a place that many of us felt a great deal of kinship in part because we built such strong relationships, and we built and discovered our own identities … at Wooster.”

“Representation matters. And Wooster needs to strive to talk about its own history and to make amends for past wrongs,” Johnson said. “I think it’s never too late to recognize the historical wrong of Susanne Woods’ forced withdrawal, and I would urge the new president to think about the opportunity she has to make right and to make clear what Wooster stands for today.”

The diligence of reporting and editing in this article [is] extraordinary. So is the attention to archives, allowing sources living and dead to speak for themselves. It takes such skills as these student journalists exhibit to confront a grievous wrong that some sought to erase not only from the College’s history, but also from our memories. Here is showcased the very best of Wooster education at work, piecing together hard truth about one of the worst chapters in the life of the College. It takes brave journalism like this to reckon honestly with painful facts.